Text by Anastasio Koukoutas

A video clip which was recently shared on YouTube anticipating the celebrations of the 200 years since the outbreak of the Greek Revolution (1821) and the Independence War against the Ottoman Empire, raised again the troubled relation between choreography and politics, or to put it more accurately, highlighted how “politics (still) emerges as choreographic activity” [1]. Politics as choreography adheres predominantly to modernist mass events and festivals but also echoes notions in political philosophy and neoliberal capitalist societies that link movement to (hyper)mobilization—thus offering an understanding of how movement can be activated both aesthetically and politically to reinforce what Niki Loizidi states as the “illusion of progress and accelerating course towards a better future” [2].

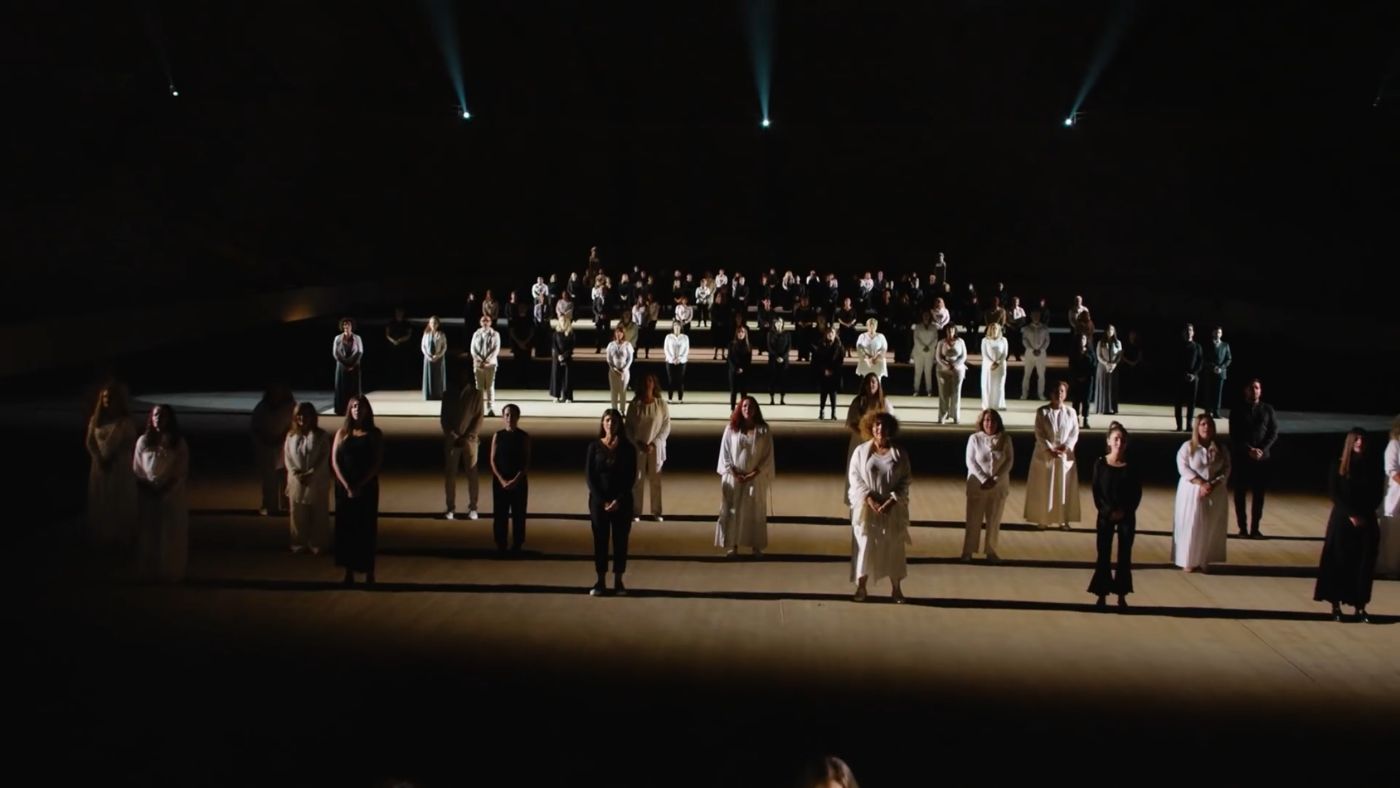

The video opens with the view of the Panathenaic Stadium (also known as Kallimarmaro) from above, resembling an empty stage that will soon come to life with the presence of a choir. A large group of people singing “Let dances carry on” by Greek songwriter Dionysis Savvopoulos is the perfect symbolization of a nation in unity, urging us to tune in with the uplifting, glorious and celebratory theme of the song. The use of the song in this particular occasion marks a conjunction of past and future by surpassing the present moment: a moment of crisis, societal precarity and political turbulence. Everything in the filming of the video corresponds to the idea of a social body performing rigorously but nonetheless spontaneously—especially in close-ups, which show people smiling all the time—so that the whole event is perceived through the lenses of enthusiasm and vitalism, as if the stadium was full with a cheering crowd. This created sense of ‘liveliness’ is both convincing and deceptive (or even convincing because it is deceptive); it stresses that if choreography is an apparatus “distributing the visible and the invisible, generating or eliminating an object, which cannot exist without it” [3], then the choreographic isn’t merely referring to a repertoire of gestures and movements that the people are assigned to perform, but also to a re-distribution of the significations these movements carry, specifically those contributing to the instrumentalization of pluralism, democracy, citizenship.

However, if “choreography doesn’t simply inscribe itself in time and space but rather transforms both time and space and bring into existence a ‘world’” [4], then we shouldn’t just (mis)judge the video from the generic choreography it contains or its kitsch aesthetics, but rather focus on how a (refurbished) ancient monument like the Panathenaic Stadium, symbolically laden with the 1890s revival of the Olympics and the agonistic ethic of sports, and a song from the 1980s by Savvopoulos, referring to the unpretentious gatherings of small groups and the untroubled enjoyment of life as typically Greek pride, construct a conception of contemporary Greece which is constantly relived through its glorious past and persistently redirected to an unfulfilled future. The above utopian sketching of a country in stillness between past and future, reinforces what we might call “the historical hegemonic arrest of dance in an aestheticizing image” [5]. This aesthetic burden is typical of the modern dance subject who searches the unique, authentic experience in her body but sooner or later (without realizing it) her body becomes the best workforce prone to exploitation. Thus, if society is somehow depicted in the video, then it is a version of society dancing its ignorance, in the dark we might say; one claiming a revival of the insouciance of the 1980s and the heroic activism of the fighters of the Independence War. The paradox is not a matter of aesthetics per se, but how the above references, by being politically exploited (anticipating maybe a success story just as the Opening and Closing Ceremonies of the Olympic Games in 2004), they adhere to a narrative that contradicts the very essence of independence and freedom—concepts which should remain at the heart of this celebration and ought to be represented differently today.

In a way, “‘contemporary’ already sets up a scene (perceptual, linguistic, theoretical even choreographic) where dance rehearses and performs particular modes of appearing-to-belong to ‘our’ time” [6]. Indeed, the negation of this contemporaneity confines us to the logic of an epoch defined exclusively from the revival of a golden past—that of a nation fighting for its independence—and the revival of a not-so-far past—the one attached to the golden days of the Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK), which in many ways has contributed to the current national identity of the Greeks. If choreographies, as mentioned above, are considered an apparatus that seize bodies, both individual and collective, to turn them into what Foucault called ‘docile bodies’, then the mise-en-scène of the specific event and the materiality of its context (song, stadium, conventional participation of artists as citizens) give an account to what we might call the commodification of the current democratic body. An implication not just noteworthy but above all worth subverting, if we think of how “golden” was the promise of a criminal organization that worked disguised as a political party and threatened the very foundations of our democratic society. If there is a moment to celebrate about today, let it be the one that marks the victory of the people and the conviction of Golden Dawn.

References

[1] André Lepecki, From Partaking to Initiating: Leadingfollowing as Dance’s (a-personal) Political Singularity in Dance, Politics & Co-Immunity, eds. Gerald Siegmund & Stefan Hölscher, diaphanes, 2013

[2] Niki Loizidi, Body and Sport as Institutions of the Aesthetic Ideology of Modernism. The Body, Sport and Modern Architecture (The notebooks of the Modern), ed. Panayotis Tournikiotis, futura, 2006

[3] Giles Deleuze, Foucault, Bloomsbury, 2006

[4] Andrew Hewitt, Social Choreography: Ideology as Performance in Dance and Everyday Movement, Duke University Press, 2005

[5] Bojana Cvejic, On the Choreographic Production of Problems in Dance, Politics & Co-Immunity, eds. Gerald Siegmund & Stefan Hölscher, diaphanes, 2013

[6] André Lepecki, Choreography as Apparatus of Capture, The Drama Review, Vol. 51, pp. 119-123 (Article), The MIT Press, Summer 2007